Dina Rose, Ph.D., author of It’s Not About the Broccoli, suggests trying the taste-and-rate approach to get your kids to try new foods. The process exposes picky eaters to new foods and reveals their inner food critics.

A great way to help your children become more comfortable tasters is to turn them into food critics. Present tiny samples of food for your children to test, and then invite them to tell you what they think. I love this strategy because it neatly removes the usual fear, pressure, and control struggles that pop up when new foods appear. It teaches kids to make better predictions about food, gives them a more precise food vocabulary, and repeatedly but gently exposes them to new foods until the foods become friendly and familiar. And kids love to tell you what they think!

A great way to help your children become more comfortable tasters is to turn them into food critics. Present tiny samples of food for your children to test, and then invite them to tell you what they think. I love this strategy because it neatly removes the usual fear, pressure, and control struggles that pop up when new foods appear. It teaches kids to make better predictions about food, gives them a more precise food vocabulary, and repeatedly but gently exposes them to new foods until the foods become friendly and familiar. And kids love to tell you what they think!

Research backs me up. In a Louisiana State University study, a group of fourth- and fifth-graders were given cups containing samples of green bell peppers, tomatoes, carrots, and peas. Afterward, the researchers asked the children how much they liked each of the four vegetables. Over 10 weeks, the children tasted each vegetable 10 times. By the eighth or ninth tasting, the kids were much more likely to like what they tasted. There were a lot of ups and downs across the tastings, but the overall trend was toward liking the vegetables.

Ready, Set, Taste

Transforming your child into a food critic isn’t hard. Your efforts don’t have to be systematic or scheduled. But, as always, you do have to talk to your child about what you’re doing and why. Talking to your kids is where the learning begins. Well before you ask your child to taste anything, have a simple conversation during which you talk about the importance of learning to try new foods. Don’t worry that an open discussion will somehow derail the system. To the contrary, it will bring your child on board. After all, every day parents teach their children things they don’t want to learn (brushing their teeth is one example that quickly comes to mind), and children accept the lessons. Give your child ample opportunity to express her feelings, fears, and concerns. Then problem-solve together. For instance, let’s say your child is worried that you’ll make her eat the food she’s tasted. You can take this opportunity to reassure her: “I know in the past I’ve asked you to eat new foods. I’m sorry, and I won’t do that anymore. I’ll never make you eat anything you don’t want to eat. Let’s go into the kitchen, and I’ll show you how small the tastes I’m going to give you will be.”

This is a good time to stress that your only goal right now is to make your child comfortable tasting new foods. The more rigid or restricted your child’s eating, the more you need to focus her attention on the big picture. “Remember when we went on vacation last year and you had a hard time finding something to eat because nothing looked familiar? Even the chicken nuggets seemed different. Wouldn’t it have been good if you were comfortable tasting new foods so you could have given those nuggets a little taste?”

Once you’ve paved the way with a conversation, the rest is easy. Just start looking for opportunities to have your child taste something new. Some parents like to have their kids taste a new food just before dinner, when the kids are looking forward to eating and the parents are already working in the kitchen. Others prefer times that do not carry a history of pressure and stress. Mornings, if they are not too rushed at your house, can be a great time for testing and rating. Or you can take advantage of opportunities as they arise—for instance, when you just happen to be eating something your kids have never tasted. No matter when you decide to offer tastes, aim to conduct taste tests frequently. It’s not enough for the new food itself to become common. You want the experience of trying new foods to become familiar, too.

Tasting: The Foundation of the Variety Habit

When you start selecting new foods for your child to taste, remember that you don’t have to stick with vegetables and other healthy foods. Instead, stack the deck in your favor. Maybe start by taste-testing a new cookie. It’ll get your child psyched for the tasting experience. Then, if your child always eats mild cheddar cheese, try selecting another cheese that is also mild or orange. As you progress, consider alternating between easy and hard tastes. If your son likes strawberry yogurt, let him try strawberry-vanilla or raspberry one day. The next day, branch out to a more exotic flavor and texture, like red bell pepper. Don’t move too quickly, though. Make sure you move at a pace your child can easily handle.

Because the goal is to make the experience safe for your wary child, you’re going to have to think micro when it comes to the actual tasting. A single shred of cheese, one sunflower seed, or one-quarter of a pea are appropriate portions. Don’t be surprised if your child can’t actually taste such a small morsel. Tiny bites make the experience even less intimidating. Next time she’ll probably request a larger bite.

Ask your child to roll the food around in her mouth. Tell her she has your permission to spit out the food if she wants to. Tasting an unknown food is a risky proposition if swallowing is your only option. Spitting instead of swallowing gives kids the courage to try. (Plus, it prepares them to become wine connoisseurs when they grow up!) Pour some water into a cup and explain that when adults eat a food they don’t like, they drink something to get rid of the taste. Kids don’t automatically know to do this.

Don’t assume that if your child spits out the sample it means she absolutely hates what she’s tasted. In the LSU study, 23 percent of the children spit out the carrots, but 31 percent of the carrot spitters said they liked the carrots. I guess they just didn’t want to swallow them.

This taste-and-rate approach is probably different from anything else you’ve ever tried, and it may seem like a lot of effort. But the more you expose your children to the sensory properties of food, the more comfortable they’ll be when tasting new foods.

Ratings Cards

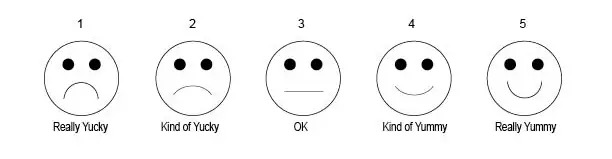

One thing you might want to do to make the tasting process more fun is help your child make ratings cards. I’ve provided an example below.

Then, after you’ve been through a question or two, ask your child to rate the food by circling the appropriate face. Be sure to meet your child’s responses with neutrality. You may want to say, “Oh, come on! You love strawberry yogurt! How can you say that this new yogurt is really yucky when it’s just regular old strawberry yogurt that is also swirled with sweet, delicious vanilla?” If you want to say something, try sharing how you experience the food. Don’t talk about how much you like it. Instead, describe the sensory experience from your perspective.

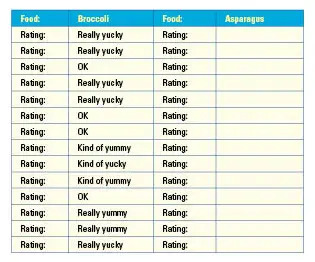

One client encouraged her child to think of this as a science experiment. She created a journal with one page for each new food, with 14 lines for each page—the number reflects how many times it takes most kids to taste a food before they feel good about it. My client encouraged her child to fill out the pages on her own. The journal pages looked a little like the one shown below.

Click to download a sample journal page table |

If you try a journal, don’t get hung up on making sure each page is filled from top to bottom. Instead, talk to your child about the need to taste and re-taste foods. It’s kind of like rereading a book. Every time you dip back in, you get a new experience.

And what if your child doesn’t want to keep a journal? It’s no big deal. You don’t have to keep track to be successful. The point to the taste-and-rate approach isn’t necessarily to score a win by getting kids to taste a particular food so many times they develop a liking for it. For now, the point is simply to help kids get comfortable with tasting new things.

|

Dina Rose, Ph.D., is a sociologist and feeding expert who has helped thousands of parents teach their kids to eat right with her innovative approach to parenting. Rose has written for the Huffington Post and Psychology Today, and she maintains an active blog on her website: ItsNotAboutNutrition.com. Rose lives with her husband and daughter in Hoboken, NJ. This article was reprinted from It’s Not About the Broccoli by Dina Rose, Ph.D., by arrangement with Perigee, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, a Penguin Random House company, Copyright Perigee Books. |

|