On a brisk

Monday morning in a classroom in Chelsea, ten children are gathered in a

semi-circle singing “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star.” They smile widely at their

teacher, Donna A.,

who is sitting in a chair in front of them, and softly giggle when one student

enthusiastically jumps out of his seat at the lyrics “like a diamond in the

sky.” Around them, brightly colored posters adorn the walls and off to the

side, there are labeled cubbyholes, each housing one child’s belongings. —

As the children,

who are between four and five years old, continue singing, one boy with a mop

of curly brown hair is distracted by his reflection in the mirror to his right.

He jumps toward it and makes faces, laughing hysterically at what he sees.

“Come back to

the circle. Sit in your seat nicely,” Donna and a teaching assistant remind

him.

Some of the

other children stand up and sit back down during the singing session. One

stares intently at the bright orange paper band around his wrist, which all of

the students are wearing.

“Who’s ready to

sing a solo?” Donna asks the class. One by one, eager students head to the

front of the circle to perform a song of their choice.

At first glance,

this may seem like any kindergarten classroom in a New York City school, but these children attend the

Association for Metroarea Autistic Children, Inc. (AMAC)—a National Association for the

Education of Young Children accredited school.

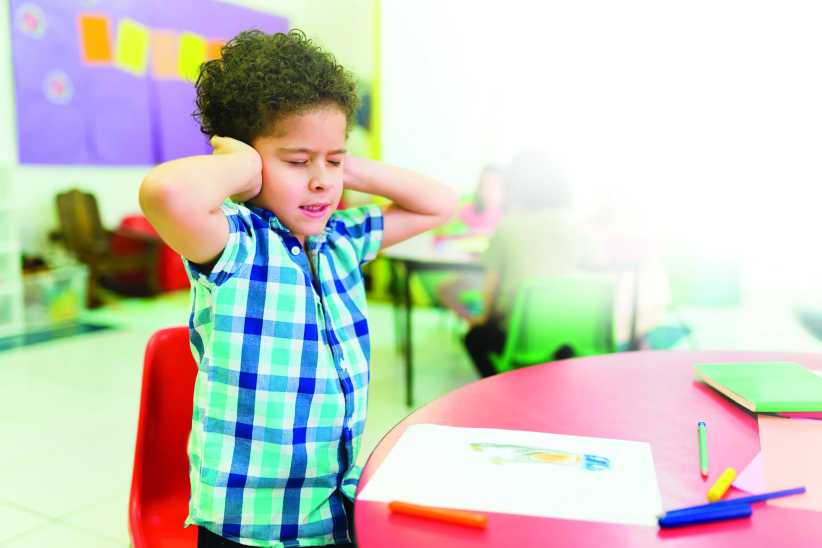

Aside from their

love of silly songs and even sillier dances, the diagnosis of autism bonds

these young children together. Categorized as a developmental disorder, autism

can cause significant social, communication and behavioral challenges.

According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, autism affects one

in every 110 children in the United States. Ranging from very mild to severe,

children with autism may suffer from delayed speech and language skills, repeat

words and phrases over and over, get upset by minor

changes or adjustments to a

routine, and have obsessive interests, among other behaviors. Although many

schools accept autistic children into their special education programs, they

are often not equipped to give these students the individualized attention they

need.

That is where AMAC comes in. Founded in 1962, AMAC is a year-round school for students ages

two and a half to 21 years old who suffer from all levels of the autism

spectrum. About 200 students attend the school, where classes remain very small

and children are placed based on their individual needs. Class size ranges from

six to ten students, all with a teacher and at least one teaching assistant.

Children with severe autism are placed in the smaller groups with greater

supervision.

“The small class

size really allows teachers to work with the students and give them the proper

amount of attention,” Miriam DiOrio, Director of Clinical Services at AMAC says. “In [certain] classes, they are

often able to work one-on-one with the children.”

AMAC teaches students not only academic

subjects, but also social and communication skills. This is done through the

Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) approach, a scientifically based, state

approved methodology. It relies on intensive behavioral intervention and

teaches targeted skills and behaviors. AMAC faculty and staff, which consist of

teachers with special education certification, trained teaching assistants and

behavioral analysts, all reinforce behaviors through a reward system—hence, the

orange bracelets.

When walking

through the busy hallways of the school where students file in and out of

classrooms and teachers sing songs about moving on to a new activity, one will find

that students have their own plastic boxes filled with snacks. Each container

is individually assembled according to the child’s personal preferences—some

filled with pretzels, cookies or small candies like M&Ms.

“When students

complete a certain task, they are then rewarded with a small piece of food,

which reinforces that it is a good behavior they should continue doing,” DiOrio

says.

Depending on the

severity of the child’s condition, the rewarded task may include verbalizing a

desire or following a routine or it may be part of a learning activity.

For example,

during one of the day’s activities for the school-aged children (ages five-13),

students and teachers sit across from each other, one-on-one, and practice word

recognition. In front of the children are bowls filled with their favorite

snacks.

“Show me cat,” a

teacher assistant says to the student sitting across from him. He holds up

three pieces of paper with different words on them. When the child points to

the word “cat,” the teacher gives him one M&M.

“Good job!” the

assistant says, as the boy happily accepts his treat.

Twice a day,

children in each classroom can purchase snacks, candy and small toys from a

reward cart. They are given currency—younger children receive wristbands and

the older students get plastic fake dollar bills—periodically throughout the

day for good behavior.

When the reward

cart visits, children line up and their currency is counted. Students can

choose to purchase various items with what they have or wait until they collect

more currency for something that is more expensive.

“If there’s a

toy or item a student really wants, he has the option to save for it over a

period of time,” DiOrio says. “So students are also learning a real life lesson

– the value of saving.”

Teachers at AMAC often face challenges that those in

other schools do not. For example, children with autism often have a difficult

time coping with changes to routine.

Jessica F.,

who has taught at AMAC for the past four years, said one of her

new students has had a particularly hard time with transitioning to different

tasks throughout the day.

“He will often

throw tantrums when it’s time to leave one task and go to another,” she says.

The solution?

Finn made a picture book for the student chronicling the different activities

of his day. She took photos of him partaking in reading lessons, doing

arithmetic, taking art classes and playing games on a computer and attached

them to the pages of the book. Each time he completes an activity, he tears the

picture out of the book and knows it is time to move to the next task.

“This helps him

transition,” Finn says. “He knows he has to get through things…like math, to

get to something he likes, like computers.”

Upstairs at AMAC’s high school, a New

York State registered school that is able to grant local, IEP (Individualized Education Program) and

Regents Diplomas, things are

run in a similar manner.

Students are

rewarded for good behavior, and class sizes are determined by the teenagers’

abilities. Like any other high school, students at AMAC are taught mathematics, English, science

and social studies.

In one of the

classrooms, students are learning economics and the concept of a monopoly.

“So, basically,

it’s when one business tries to wipe out all other corporations?” a student

asks his teacher. “They’re trying to wipe out their competition.”

“Exactly!” the

teacher exclaims. “You got it.”

Just then

there’s a knock on the door. The reward cart is making its afternoon visit.

Students begin

lining up at the cart.

“How much for

the Welch’s Fruit Snacks?” one student asks.

“Four dollars,”

comes the response.

The student buys

the fruit snacks, but mutters to himself on the way back to his seat. “Four dollars

for Welch’s Fruit Snacks—that’s pretty steep!”

For parents,

being involved in their child’s education is a very important aspect of the AMAC experience. A communication notebook, in

which teachers update parents on their child’s progress, is sent home with

students every day. Parents also have the option to write notes to their

child’s teacher about any concerns they may have.

Vernalize

Cameron, whose son Mirembe, 4, has attended AMAC for the past two years, says that this

constant communication has been an integral part of her child’s education.

“Knowing what is

going on at school is great because it allows me to bring the lessons home,”

she says.

Cameron, who

praises AMAC’s system of rewards, says she continues

to reward Mirembe after the school day is over because the approach really

works.

“Before he came

here, he would constantly throw tantrums,” she remembers. “He wouldn’t want to

go outside. If he wanted something, he didn’t know how to express himself. Now,

things are so much more peaceful and he doesn’t get agitated as much.”

Yet, Cameron and

school officials emphasize that AMAC

offers much more than a strict regimen of behavior analysis and rewards.

“We also provide

a loving and nurturing environment that is warm and inviting,” says Arnold R.

Cohen, M.D., the Medical Director and one of the founders of AMAC.

Cohen notes that

in addition to regular school activities, AMAC holds a number of specialized events

that students, parents and faculty alike greatly enjoy, including fundraisers,

concerts and holiday celebrations—most notably a Thanksgiving meal that

includes homemade dishes from parents and even celebrity chefs.

“It’s quite the

feast,” Cohen says with a smile.

Perhaps it is

this mix of a proven scientific method and the warm nature of the school that

accounts for AMAC’s success. Last year, high school

student Naresh Cintron graduated and went on to attend Lehman College. Also, the entire preschool class

graduated into less restrictive schools, a goal officials at AMAC are very proud of and hope to achieve

again this year.

Cameron says she

believes her son’s experience at AMAC has prepared him to move to a mainstream

school after this year.

“He’s come a

long way,” she says, “and with everything he’s learned here, I am much more

comfortable with the idea of him attending a regular school.”

For more information, visit amac.org.

Photograph by Andrew Schwartz