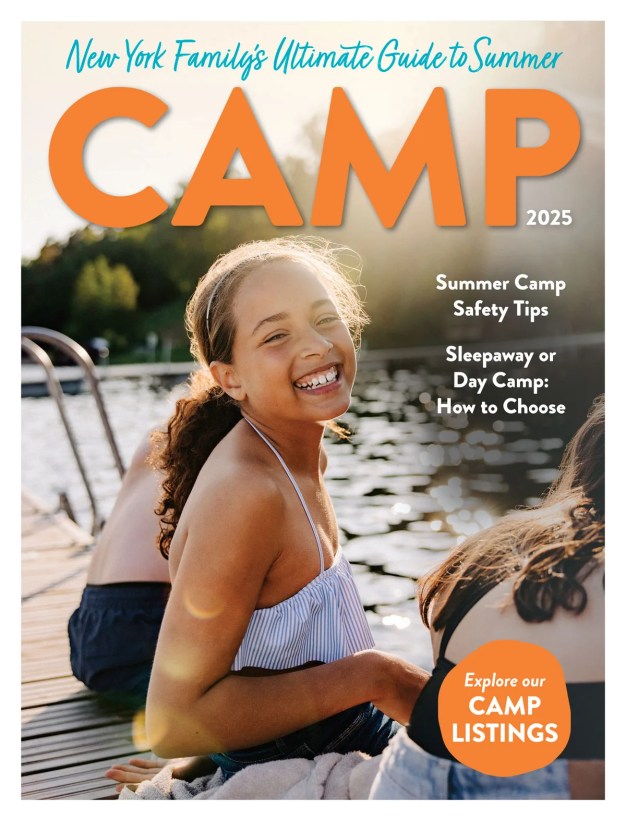

If you’re the parent of a teen who lives for anything related to camp, from the arts and crafts cabin to color wars to archery, now might be the time to talk to him about applying for a summer job as a counselor-in-training at a camp nearby. Turns out, becoming a CIT is the next best thing to being a camper because your teen will get firsthand experience and job training, and have a little fun, too.

How do I know my child is ready to be a CIT?

Your teenager may have set up many a lemonade stand or sold Girl Scout cookies, but for most kids a CIT position will be their first job. As a parent, you’ll know that your teen is a great CIT candidate if he or she is extra trustworthy. “An important question for parents to consider is, ‘Would I trust my teen to watch other people’s children?’ suggests Michael Halpern, director of Mosholu Day Camp in the Bronx. If your answer is yes, “That’s usually a good sign that you, as a parent, think that your child would be a great counselor-in-training.”

Also ask yourself how reliable your teen is, says Colleen Barnhart, camp director at Camp Claire in Lyme, CT. “When you ask him or her to do something and walk away, does it get done?” she asks. “If you continually ask them over several weeks, do they eventually do it without being asked?”

Again, if you’re able to answer ‘yes’ to both these questions, your child probably is conscientious enough to make a good CIT. To help your teen get ready for the job, give her responsibilities around the house and hold her accountable, Barnhart says. “Assign her chores, show her exactly how to do them by participating with her as a partner, and then have her do that task alone the next week. If she messes up, don’t tell her that it is not her fault. Instead, be constructive. Tell her it’s okay because she is learning and show her how to do better next time.”

There’s one more important character trait your child should have: He should really love camp. At Mosholu, for example, 95 percent of CITs are ex-campers, and supervisors there have worked up the ranks all the way from their days as campers to unit leader. “The perfect CIT is one who grew up in my camp because they know how things go,” Halpern says. “That’s even more important to us than an application filled with babysitting experience.” After all, babysitting is usually 1-on-1, while camp is all about being in a group. “The fact that you’ve been in camp means that you know about the group dynamic,” Halpern explains. “As CITs, you’re not going to be one-on-one with a child ever, so we need to know that you’ve had that experience interacting in groups.”

Last of all, make sure your teen has the right motivation for applying for a CIT job. Does he want to work with kids, or does he just want to be back at camp? “CIT work is hard work,” Barnhart says. “To know if your child is really ready to be a CIT, ask what his goals are for the summer. Be sure he’s clear on why he wants this job.”

The Qualities Camp Directors Value in CITs

One of the key qualities of a CIT is an eagerness to learn. “I want my CITs to take on a leadership role and add more responsibilities as they get experiences,” says Peter Corbin, founder and director of Corbin’s Crusaders Sports Club in Greenwich, CT, who hires five to 10 CITs each summer. “When they come to us as a CIT they don’t have a lot of experience. That’s why at the beginning we give them a taste of responsibility, and as they get more and more successful, we give them more. If they’re not as successful, we’ll give them more direction.”

The other qualities camp directors look for include good communication skills, maturity, responsibility, respect, care for others, interest in working and engaging with children, teamwork, and initiative, Barnhart says.

“At the beginning, initiative looks like being a willing buddy to a camper for trips to the bathroom or nurse,” she explains. “It’s also helping campers clean their area without being asked, and starting games with campers during downtime, such as cards, charades, wax museum, or storytelling. Initiative is one of many qualities that is important for a camp staff to function as a team, because that is what we essentially are when it comes down to it.” Familiarity with the camp can also be an important factor when a teen is hired to be a CIT, Halpern says. “We look at the type of camp they went to and if their camp was similar to ours in terms of being traditional or outdoorsy or things like that,” he says.

In the end, a meeting without the parents present is a critical part of most hiring procedures. “We like to have a conversation with teens—without their parents there—so we can speak to their maturity and their abilities to be outgoing and friendly,” Halpern says.

What Kids Can Expect From a CIT Program

As a CIT, your teen may stay with her assigned bunk or switch around the camp depending on the need for extra help. She could be asked to pitch in on a variety of tasks, such as setting up the baseball fields before campers arrive (including making sure all the equipment is in place), assisting the arts and crafts counselors, or helping the swim instructors. “Typically we give the CITs the option to either be with a group or with an activity,” Corbin says. “I’ve had CITs learn how to become swim instructors and ultimately work as lifeguards, while others tend to work with a particular age group all summer.”

Regardless, CITs should expect to always have someone supervising them. Your child should also be prepared for long, tiring days. “CITs tend to get tired very easily because they’re working the full day and may have never done so before,” Corbin says. “They realize quickly that the work isn’t always easy, but it’s also really wonderful to see their sense of pride in the job—they often tell me how cool it was to work with such and such kids, or do a particular job, even if it meant moving baseball equipment in the hot sun.”

In addition, Barnhart says that while CITs should expect fun lessons and team-building activities, they should also realize that, unlike camp itself, not every second is going to be fun. “Working at a camp is a lot of hard, sometimes gross work, especially at resident camps where we are on duty twenty hours a day, six days a week,” she says. “CITs will get tired and frustrated, but it is all part of the process of maturing and learning how to be a camp counselor.” Another thing your child needs to realize is that he will in all likelihood not get paid. CITs “are legally campers, so they pay to attend, but we write them letters for community service hours,” Barnhart says. “Other camps may pay, but none that I am familiar with.” Of course, CIT experience may lead to a paid counselor job in future years.

For some kids, it can be a bit of a transition to move from camper to counselor. Barnhart understands this. “I firmly believe in giving CITs the chance to grow into the role and rise to expectations, which is why I don’t call them ‘kids’ anymore,” she says. “They are no longer campers, except legally, so we start treating them like the young adults they are. They are never in charge of supervision but they certainly can assist us with it.”

In the end, consider this: Being a CIT is essentially one giant job interview for the next year. “We look for CITs to use feedback to grow and better themselves,” Barnhart says. “We constantly give CITs feedback on how they are doing, what their strengths are, what we would like to see more of, and specifically what negative behaviors we would like them to be aware of and change. A great CIT will often go out of their way to ask for feedback, and then take this feedback, reflect on it, and actively try to do better.”

That feedback loop is what will enable your teen to become a CIT and then, hopefully, be asked back as a counselor for a future summer.