Parental separation will always hurt children, but within the last decade, we as a society know more about the needs of children from their birth to their adolescence. Most importantly, we are aware that children need to know that the parents’ separation is in no way their fault. According to author Penelope Leach, our society may know more about the needs of children, but our legal system focuses on the needs of parents when granting divorces, and Leach has some suggestions on how parents can better help their kids through the divorce.

The author takes a look at just how divorce affects families in her 2014 book “When Parents Part.” According to Leach, the most recently published statistics concerning divorce are grim. For example, children in post-divorce households were “less satisfied” with life than children from intact families. Furthermore, separated or divorced adults had lower scores on the “Well-being Index, which covers emotional and physical health, health behaviors, life evaluation, work environment, and access to basic health necessities.”

Yet, nearly half of all U.S. marriages end in divorce. Two unhappily married adults know they don’t need to live out their lives together in melancholy. Luckily, divorces are granted by the U.S. legal system. But it still archaically focuses on the parents’ happiness and their rights to see their children. Instead, the court system should be paying attention to the needs of the children and how the children are affected by the residential and visiting arrangements of the separated parents.

Parents should find age-appropriate words to tell their child why the separation happened and ask their child how it makes him feel. Despite what feelings the parents have for each other as partners, they should muster all of their inner strength and let their children know that they are strong and not destroyed by what is happening.

Effects of divorce by age

Children experience various reactions to parental separation at different ages. Not only do parents need to be physically present, but they also need to be emotionally attentive and listen to the thoughts, feelings, and responses of their children.

For example, if two spouses separate when they have a newborn, it is now common knowledge that newborns must be with their mothers throughout the first year of the baby’s life. The father may also have contact with the newborn, and his presence will also impact the child, but if a new baby can bond and create a strong attachment with its mother during its first year of life, the more secure it will feel in the future.

The mother, again, cannot be emotionally vacant. If the baby cries, she must pick the baby up and try to soothe him. The baby can sense if the mother is upset, and thus, its attachment to the mother can break apart.

A legal system insisting on “equal or shared parenting,” meaning that both the mother and the father have the same amounts of shared time with the newborn, puts the priority of the parent before that of the child who is shuttled between both caregivers In that case, the attachment between newborn and mother is put at risk.

During a baby’s second year, it forms an attachment with the father, but the baby will still stay physically attached to the mother until its fourth birthday. In the best interests of the child, the father can visit a toddler during the day when it is 2 and 3 years old.

A child will not be willing to leave his mother overnight until he is 4 or 5 years old. The more securely attached the child is to the mother, the better able the child will be to spend the night with the other parent. It is important that a parent not confess all her feelings to a toddler. Let the child know, however, that parents aren’t perfect, and things will get better.

When children enter elementary school, the parents’ separation has yet another adverse effect on them. This is the age when children personally feel rejected by the parents who seek separation. Children at this age are also very frightened about what is going to happen to them.

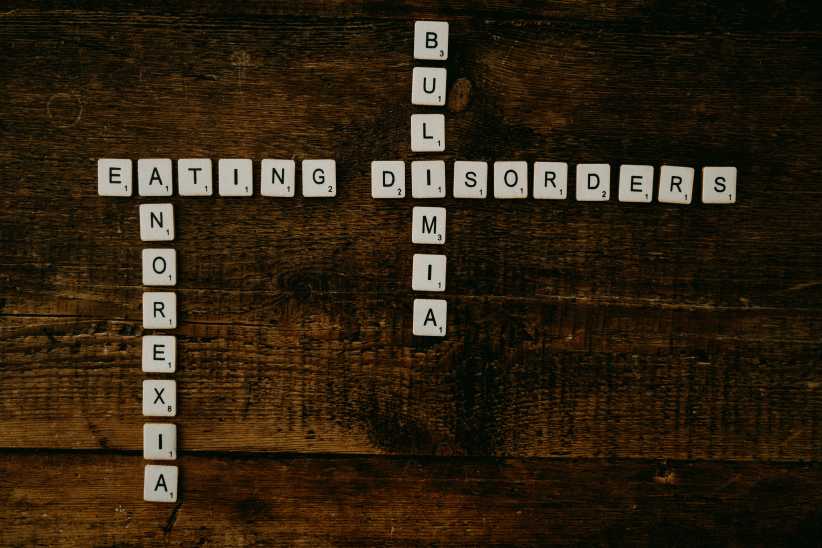

Adolescents and teenagers react by spending more time with their peer group to see if other families act “normally.” According to Leach, if they are not carefully supervised, the probability of them engaging in high-risk behavior, such as drinking or taking drugs, increases. Sometimes parents wait until their teenagers go to college before they divorce. Unfortunately, these adolescents then view their whole childhoods as a lie and are less likely to confide in their parents in the future.

Leach provides a lot of practical advice for separating couples, such as advising parents to keep a consistent daily routine at home if the children are suffering from separation anxiety. Children should be informed of any changes to their schedule or if a visitor is coming to stay at the home. Leach also suggests that a parent invite other single-parent families to share holiday celebrations and vacations where everyone will be able to help each other out.

Mutual parenting

What Leach does believe in is the idea of “mutual parenting,” which is that each parent supports the relationship that their ex-partner has with each of the children and to protect the children from the failure of the relationship. Children notice and care about what is happening to their parents, but a child should never feel “motherless” or “fatherless.”

Mutual parenting is about not allowing an ex-spouse’s hurt feelings from changing the way she sees the other parent as a capable and loving caregiver to their children. Never use a child as a confidante to discuss feelings, she warns. When parents are committed to putting their children’s happiness first, they are in joint communication about scheduling arrangements and discussing information about their children.

If parents are unable to support each other in “mutual parenting,” Leach suggests, then the next step they should take is “polite parenting,” where they follow the arrangements of an agreement to the best of their ability. They do not deliberately alienate their children from each other.

It is against the law for one parent to ruin a child’s relationship with another, according to Leach. When one parent thinks the other is unfit, it is easy to make an allegation of abuse, addiction, or dangerous neglect. Wildly exaggerated accusations, however, may damage rather than protect the children.

Even if a parent cannot take care of her children on her own, she is still able to have a loving relationship with them. The other parent should, nevertheless, be honest with the children about the ex-spouse’s inability to parent the children.

Most recently, the U.S. legal system has begun to take into account the rights of the children when it emphasizes quality over quantity parenting. When children are shuttled between houses to ensure that both parents have equal time with them, everyone’s schedules are upended. Leach suggests it is easier for children to spend the week with the resident parent while attending school and spend the weekend with the non-resident parent.

Fathers often ask for more contact, especially overnight visits from children, because they fear they will fail to build a close relationship with their children, says the author. Research has shown that these fears are “groundless” because the “quality of contact — parent and child looking forward to seeing each other and having fun together — is far more important than quantity,” writes Leach. Parents also think that bonds with their children will become closer during overnights, but recent research has again shown that daytime-only contact does not reduce attachment.

Many studies show that children, adolescents, and adults who have close relationships with their fathers do better in school, at work, and in their social lives than those who do not. Such research shows that fathers are just as important as mothers to children.

According to Leach, when the family unit breaks, separated partners should “muster selfless concern for the children … That selfless concern can keep them united in their determination to carry on being and helping each other be loving parents … No longer a wife, husband or partner, but always and forever a mother or father.”

Allison Plitt lives in Queens with her daughter and is a frequent contributor to this publication.