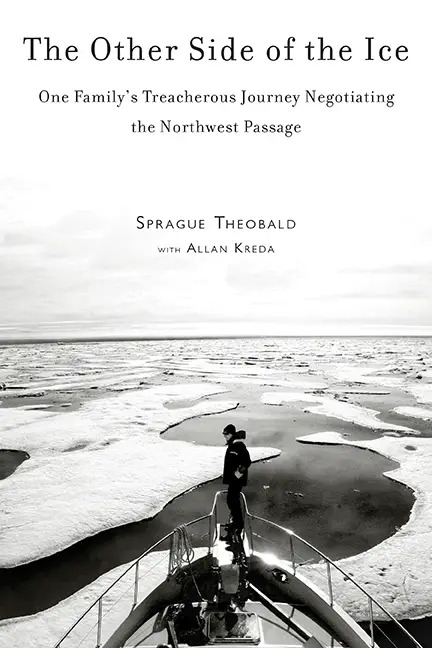

A divorced Manhattan father reunites his three grown children for a risky trip to the Arctic. As their boat navigates a place few others have ever been, they find themselves on more than a physical journey.

We were hundreds of miles from help. We were high in the Arctic, in uncharted waters. Ice was moving in from the north and would soon have us in a death squeeze with the ice fields in the south. We hadn’t seen another boat or person in almost three weeks. One thought kept rolling through my mind: Have I brought my children together only to lead them to their deaths?

Six weeks earlier I had left Newport, RI aboard my 57-foot trailer, Bagan, bound for the Arctic’s infamous Northwest Passage. It would be a five-month, 8,500-mile trip—if we made it. Known as a ship-killer, The Passage is a theoretical shortcut between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, and hundreds of men have died trying to find this maritime Holy Grail. As a filmmaker, writer, and avid boater with approximately 40,000 offshore miles to my credit, I had traveled from Alaska to Zanzibar finding stories for my fledgling production company, Hole In The Wall. But nothing could possibly prepare me for those five brutal months trying to find what very few before me have managed to find.

|

The Bagan, at sea |

Miracles in life happen far more often than we give them credit for; we just don’t keep our eyes open often enough. One of the biggest, if not indeed the biggest for me, happened a few months before our team was to set out. Fifteen years earlier my family had gone through what so many do—a divorce, which, albeit non-contentious, was brutal on my son, two stepchildren, and myself. During that time, my son, Sefton, and I got together as often as possible (still not nearly enough). I saw my stepdaughter, Dominique, far less, and my stepson, Chauncey, less still—in fact, not once. In a tragic event like divorce, hurt seeps into every corner and crevasse and, once there, takes its sweet time to painfully trickle out. I lay down at night hoping I did the best that I could but as all parents know, there’s a chasm between “best” and “far better.” That’s why I jumped at the chance to have my kids come with me on the Arctic trip.

Over the years Dominique and I had done many offshore miles together on various boats. Once I plotted our course, she was not surprisingly the first crewmember who signed on. She and I, along with a small handful of others, spent two years prepping Bagan for every hazard we felt we might encounter.

Two months before our scheduled departure, Sefton found out that he could get the first semester of college put on hold, which would free him up for the entire summer and fall. This was the best news I’d ever heard, since it meant he could do the full trip, not just a small leg of it.

A week after that, Chauncey was laid off from work and suddenly found himself with a wide-open schedule. Despite the fact that Chauncey and I had not spoken with one another for more than a decade, he courageously approached me about the trip. He didn’t have much in the way of offshore experience but had a work ethic and attitude second to none. I checked with Dominique to see if we could handle a sixth aboard, and Chauncey was confirmed to join us in Greenland.

Within a few very short weeks, this family that had not been physically together for almost 16 years was going to be together on a boat for five months. What astonished me most about reuniting with my children was that, throughout the trip, there were no moments of, “Remember the time you yelled at me…” or even “Why did you and Mom split?” I had the clear sense that all three kids were able to observe who I was in times of action and stress. Here they could get their truest sense of their father and stepfather. That’s certainly how it was for me: Yes, I could see the child in each and every one of them—like the joy in their eyes when we turned an uncharted corner and saw a small pack of polar bears doing what polar bears do when not behind glass walls.

We were put to the test of survival when we became trapped between deep, powerful converging ice floes for two very long days. Judging by what we saw happening all around us, it would be a matter of hours before we and our fiberglass boat were simply crushed. As a group we had to decide to toss the captain off the boat for abusive drinking and an attitude that was beyond cowardly, bordering on criminal. All three ‘kids’ showed me then who they were.

Why did I almost lead my children to their deaths, I can all but hear you asking. The decision to come on a trip which held no guarantee of a happy ending, first and foremost, was theirs and theirs alone. The fact that they would consider joining the effort was a parental joy to me, but at no time did I try to paint a rosy picture for them. Quite the opposite: I told them, frankly, we might not make it back. But as their enthusiasm grew I realized that if I could get them all together, we would have a chance to see where we stood as a family—and, moreover, where we were headed as individuals.

What we were all subconsciously hoping to accomplish was to reestablish the connections we’d abandoned years before. Regardless of the silences over the years, I was confident that, for me at least, love was abiding. A foundation of respect and honor was firmly built in those early years we were together. It was my hope that the extremes of the trip would reawaken these emotions, and that maybe, just maybe, we could pick up where we left off. We did.

“Could you keep the laughing down?” I yelled on numerous occasions. “I can’t sleep!” The moment those wonderfully absurd words tumbled out of my mouth I joined in the kids’ laughter, sharing a prized emotion; sleep could wait. During five months of brutal, hellacious travel, there was not one word of anger or resentment from any of us.

As a team we suffered all sorts of hardships that summer: cramped quarters, lack of privacy, extreme cold, polar bear threats, mechanical issues, extreme wind and 10-foot waves, rogue ice floes, uncharted waters, and a perilous crew conflict. And yet, we made it.

No words can adequately express how each of us felt as we stepped foot onto the Seattle docks on Nov. 9, 2009. We had done what very few had ever managed to do before: As a family, we picked up some terribly broken pieces, and without blame, justification, or defense, assembled them anew. One journey ended, and another began.

The Other Side of The Ice by Sprague Theobald