There I was in town the other day, running errands while listening to music on my iPhone with earphones plugged into my ears. The music, though, suddenly stopped, and I started hearing my 10-year-old daughter singing, “I love you. I love you. I love you.” Completely perplexed, I looked down at my playlist of songs and saw the words “Voice Memo.” Somehow, my daughter decided to create her own song and inserted it into my playlist.

I was astonished she could do this at 10 years of age, because I’m well into my 40s and cannot figure out how she managed to accomplish it. At her top-rated public elementary school in Queens she learns about various websites in her technology class, which teaches students more about computers. A couple of the websites (www.code.org and www.scrat

Now my daughter is in fourth grade and is in a STEM class — an acronym for “Science, technology, engineering, and math.” It is the first STEM class the school has ever had, and I had no idea she had been chosen for it until her first day of school. Because there are so few Americans, especially women, in these fields, STEM classes are now being created in schools throughout the country.

Every few weeks, the kids are put into teams of four and asked to do a task: mail a potato chip in a package that will prevent it from breaking; balance a marshmallow on 20 vertical spaghetti sticks; drop an egg with a parachute to ensure it doesn’t break; create a survivor team to escape from any region of New York state with just a handful of tools; build a tower using index cards and tape; or construct an Iroquois Native American longhouse from a design plan and materials the children had to prepare and gather beforehand.

After every project, all the students are asked to write about their experiences working on these assigned tasks with their teammates. I read over my daughter’s summaries, which usually start out with “We all had different ideas.” Then the essay gets juicy, because “two people disagreed and got into a fight.” Every paper, however, calmly ends with “In the end, we found out which of our designs worked best.”

There was quite a bit of drama with the interpersonal dynamics of the groups when these projects started in September. Now, many months into the school year, my daughter doesn’t come home complaining that no one listened to her ideas.

I am grateful towards this school for giving my daughter such a comprehensive education. I am also happy that with each passing year, my daughter becomes more and more eager to go to school in the mornings. I have just a few qualms with the curriculum — a result of my old-school background, when computers weren’t in classrooms, and we spent more time using pencils.

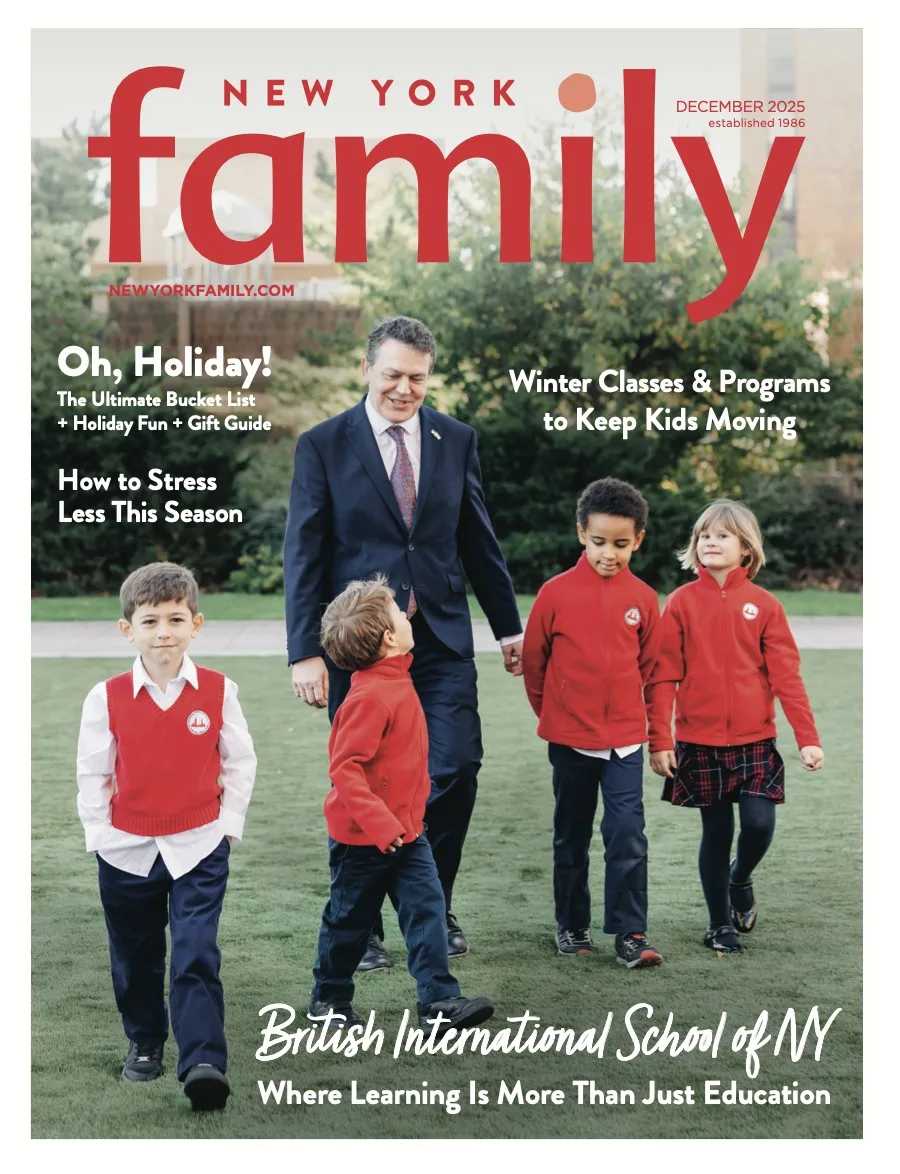

My first complaint, over which I hear many parents also grieve, is the loss of cursive writing. It’s still taught in some private schools in the third grade, but teaching cursive handwriting has been completely eliminated from the curriculum of public schools across the country. Families who value traditional skills like cursive often explore Private Schools in New York City, where some programs continue to emphasize handwriting and classic learning foundations. The subject was brought up at a Parents Association meeting at our school and labeled a lost cause, as one parent, a Human Resources Director, recalled asking a teenage intern to sign her name on a document and all she wrote was the letter “X.”

My second criticism is that many New York City public schools stop spelling tests after second grade ends. I remember being in a spelling bee in sixth grade, when we still had to memorize 10 new spelling words a week. As other parents have spoken to me about their children’s problems with spelling, I asked at a Parents Association meeting that the idea of continuing the spelling tests past second grade be brought up at the School Leadership Team meeting, when a group of teachers, parents, and the principal of the school meet on a monthly basis.

When I asked my friend who sits on that team about my spelling test suggestion, he said the teachers didn’t think spelling tests were necessary, as spelling was already embedded into the children’s curriculum. I still fume about this response, but I can still manage a hearty laugh at the end of the school year when some of the kids sign cards to each other saying, “Have a happy sumer.”

My last worry is that teachers are not given the respect that they deserve in the classroom. My daughter is not the top student in class, but she always gets high marks for her behavior. I have heard my daughter and her own teachers complain that students continue to talk after they have been told to be quiet. Even when the principal visited my daughter’s class to intervene, the students continued to talk.

Last year, my daughter came home from her third-grade classroom complaining that so many kids were talking, she could no longer hear the teacher speak. As the class parent, I sent an email to all the parents and instructed them to tell their kids to stop talking in the classroom. I also wrote in the email that I had a list of kids who were talking, and if they wanted to know if their child was on the list, they could contact me.

Of course, I was punished by the teacher for making her look incompetent, and several of the parents complained about my interference in a job that was not mine to do. It had just gotten to the point for me where I had seen and had heard enough.

Surprisingly, there were quite a few parents supporting the fact that I had addressed the issue so openly. For the past two years, there have been 32 students in my daughter’s class, and even with a teacher and an assistant, it is still not enough supervision to get the kids to behave.

In retrospect, I still cling to the love letters my grandparents wrote to each other in cursive writing and sigh in exasperation as my daughter continues to incorrectly spell “February” — until she sees it auto-corrected on the computer. With all of this new technology and teaching techniques to encourage experiential learning in the classroom, we, as a country and a community, have forgotten to teach our children the thing that matters most — showing respect towards others.

Allison Plitt is a writer who lives in Queens with her daughter.